Every ambitious project begins with confidence. On paper, everything seems to add up. Yet, from ancient monuments to modern megastructures, large projects have a habit of collapsing under their own weight. Is it because of their monolithic architecture, or are there other factors at play?

When a business grows, the main question becomes: “Should we continue with our traditional structure, or adapt it to meet the company’s evolving needs?” In this article, we’ll explore why giants fail, how size hides complexity, and which architectural approaches can help manage and design large-scale systems effectively.

The tar pit of large projects

History shows a stubborn pattern: the bigger the project, the more likely it is to stall, spiral, or collapse entirely. Here is how Frederick Brooks describes it in his book The Mythical Man-Month: “In the mind’s eye, one sees dinosaurs, mammoths, and sabertoothed tigers struggling against the grip of the tar… Large-system programming has, over the past decade, been such a tar pit, and many great and powerful beasts have thrashed violently in it.”

Almost 50 years have passed since Brooks’ book was released. The century has changed, and a new millennium has arrived. Yet, despite all technological advancements, we can say the same thing today: right now, as you read these words, some massive project is dying, sinking into that very same “tar pit.”

According to a 2020 Standish Group study covering over 50,000 projects worldwide, only 31% were completed on time, on budget, and with full functionality. Half of them were delayed or went over budget, and 19% were never completed.

The fact is that the chance of success here is lower than flipping a coin and guessing heads or tails. The worst part? The larger the idea, the lower the odds. For example, the Standish Group study shows that small projects succeed 51% of the time, while medium and large ones succeed 22% and 13% respectively. It happens because complexity increases not linearly, but exponentially. And exponential growth is hard for our linear minds to grasp.

Let’s recall the legend about the chessboard and rice grains. Long ago, the creator of chess asked the ruler of India for one grain of rice on the first square of a chessboard, doubling the amount on each successive square. The ruler thought it was modest until the grains exploded to over nine quintillion by the 64th square. The same applies to large projects. They require more and more resources, and at some point, their growth becomes uncontrollable, leading to failure.

Exponential growth lessons from history and modern times

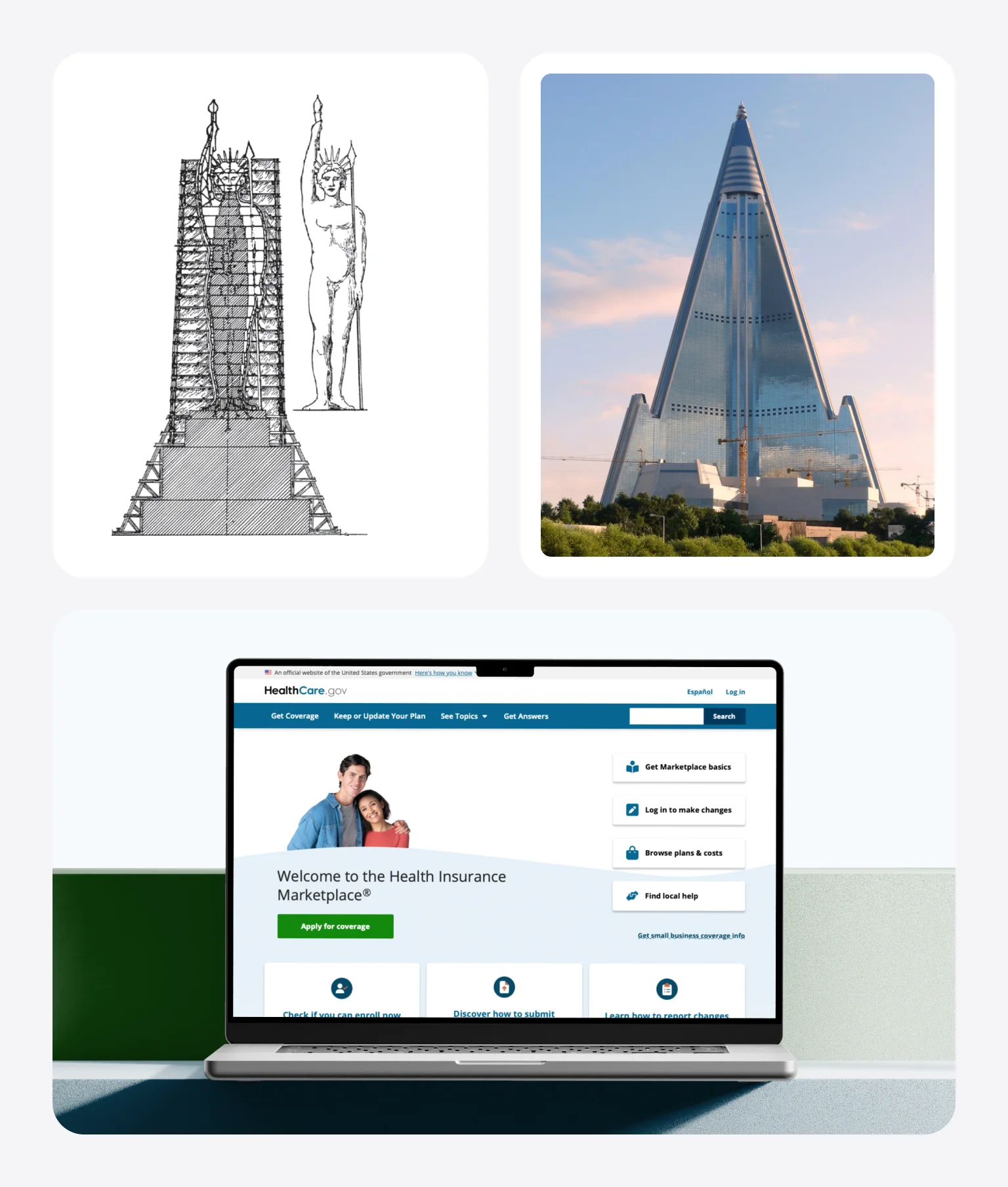

People encountered the non-linear relationship between size and resources as far back as antiquity. When the inhabitants of the island of Rhodes decided to build a majestic statue — one of the Seven Wonders of the World — they initially planned for it to be 18 meters high, ten times the height of a human. However, they managed to raise twice the planned funds, so they decided to double the statue’s height.

The calculation was wrong. A statue is a 3D object, not a linear one. Suppose you double the height, the volume and weight increase not by a factor of 2 but by a factor of 8. The Colossus was eventually finished, but to complete it, the sculptor had to borrow massive amounts of money, went bankrupt, and ended up in a debtor’s prison. This example clearly illustrates how underestimating complexity can lead to catastrophic consequences. And if anyone thinks this was just ancient Greeks being bad at math, we can still see the same thing in modern development.

Take the 105-story Ryugyong Hotel in Pyongyang. This structure, intended to be one of the tallest in the world, has been under construction since 1987 and remains unfinished. In 2024, the North Korean government once again began searching for a contractor willing to complete it.

Or consider the HealthCare.gov, the U.S. health insurance website. The planned budget was $95 million. In the end, the development cost skyrocketed, totaling over $2 billion. What do these projects have in common? The sheer size.

When the project becomes large

As a system grows, certain warning signs start to appear that indicate the architecture is struggling to scale with the project and the organization. Here are the things you should pay attention to when your project is getting bigger:

- Releases take weeks instead of days. It happens because testing, coordination, and deployment are slow and risky.

- A small change breaks unexpected parts of the system, revealing hidden coupling and poor boundaries.

- Teams block each other as they work in the same codebase or depend on the same release cycle.

- A single bug or failure can bring down the entire system instead of being contained.

“There is a hard limit to how many people can work effectively on a single whole. The solution is to divide complexity, not fight it.”

Take Netflix as an example. In 2008, the company experienced a major outage that took large parts of its service offline for several days. While this incident wasn’t the sole reason for change, it exposed critical weaknesses in their architecture and operational model.

As the company grew and shifted toward streaming at scale, those limitations became impossible to ignore. Over the following years, Netflix gradually moved away from a centralized monolithic system toward a cloud-based architecture composed of many independent services. This evolution gave them the speed, resilience, and autonomy required to innovate at scale, even though it introduced a new set of complexities. This brings us to the next part of this article: the difference between monolithic and microservice architectures.

Microservices vs. monolithic architecture

Every manager’s instinct when a project falls behind is to add more developers. It’s logical, intuitive, but what if adding more hands to a project is actually completely wrong? Let us explain to you the reasons behind it.

When 1 + 1 ≠ 2

The issue with large projects, at least in software development, is that you can’t solve the problem by simply throwing more developers at it. Frederick Brooks was the one who identified this pattern. Now, it’s known as Brooks’ Law, which goes: “Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.”

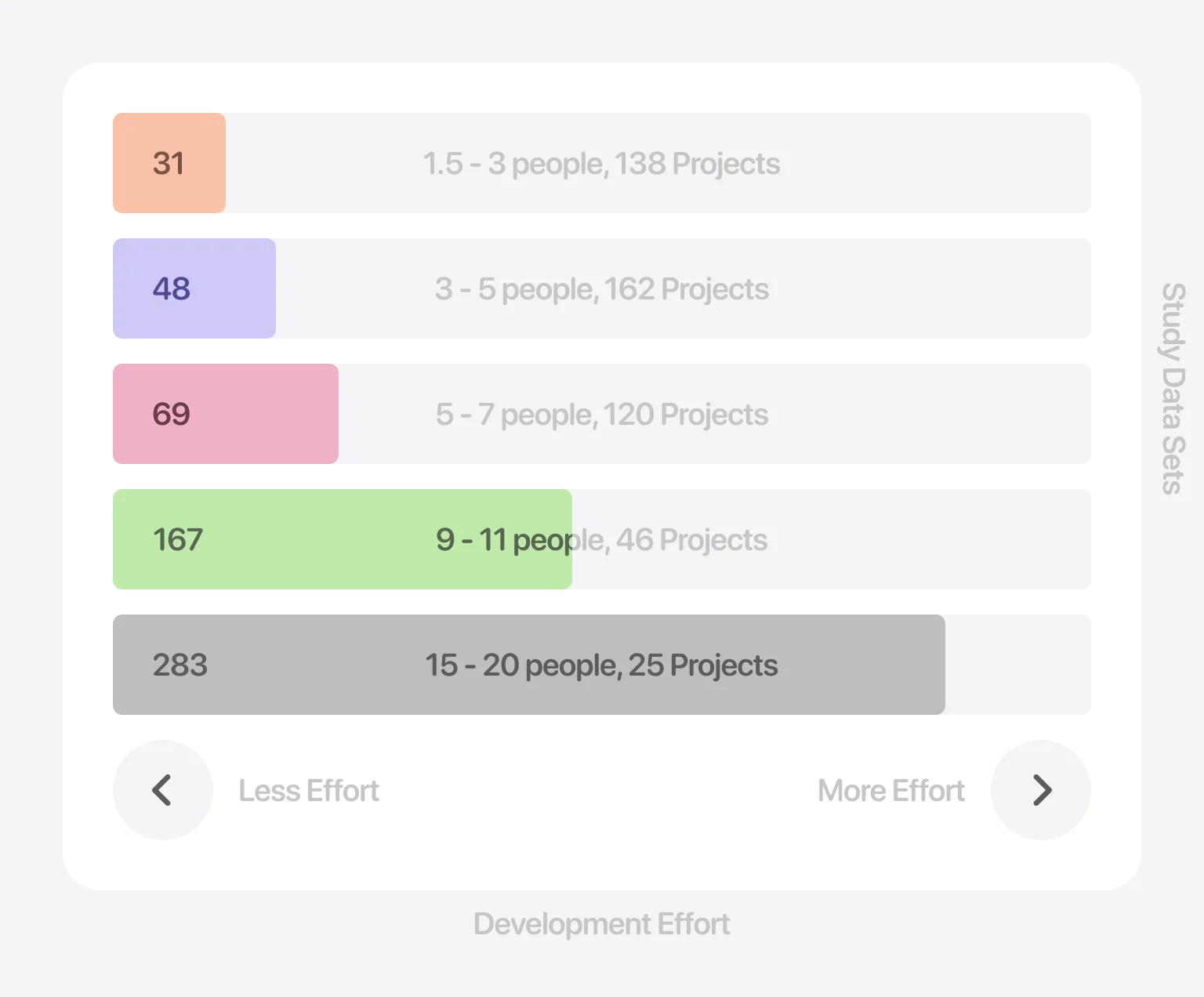

It turns out that the most productive teams consist of 1–3 devs. The larger the team, the lower the individual productivity of its members. Furthermore, adding people quickly begins to slow down the project entirely. This happens because new workers need to be onboarded, which takes time away from the experienced developers already working on the project.

But if you can’t simply expand the team, you can try splitting a large project into small, autonomous modules and developing them independently. This approach is the foundation of microservices architecture.

The skyscraper and the modular town

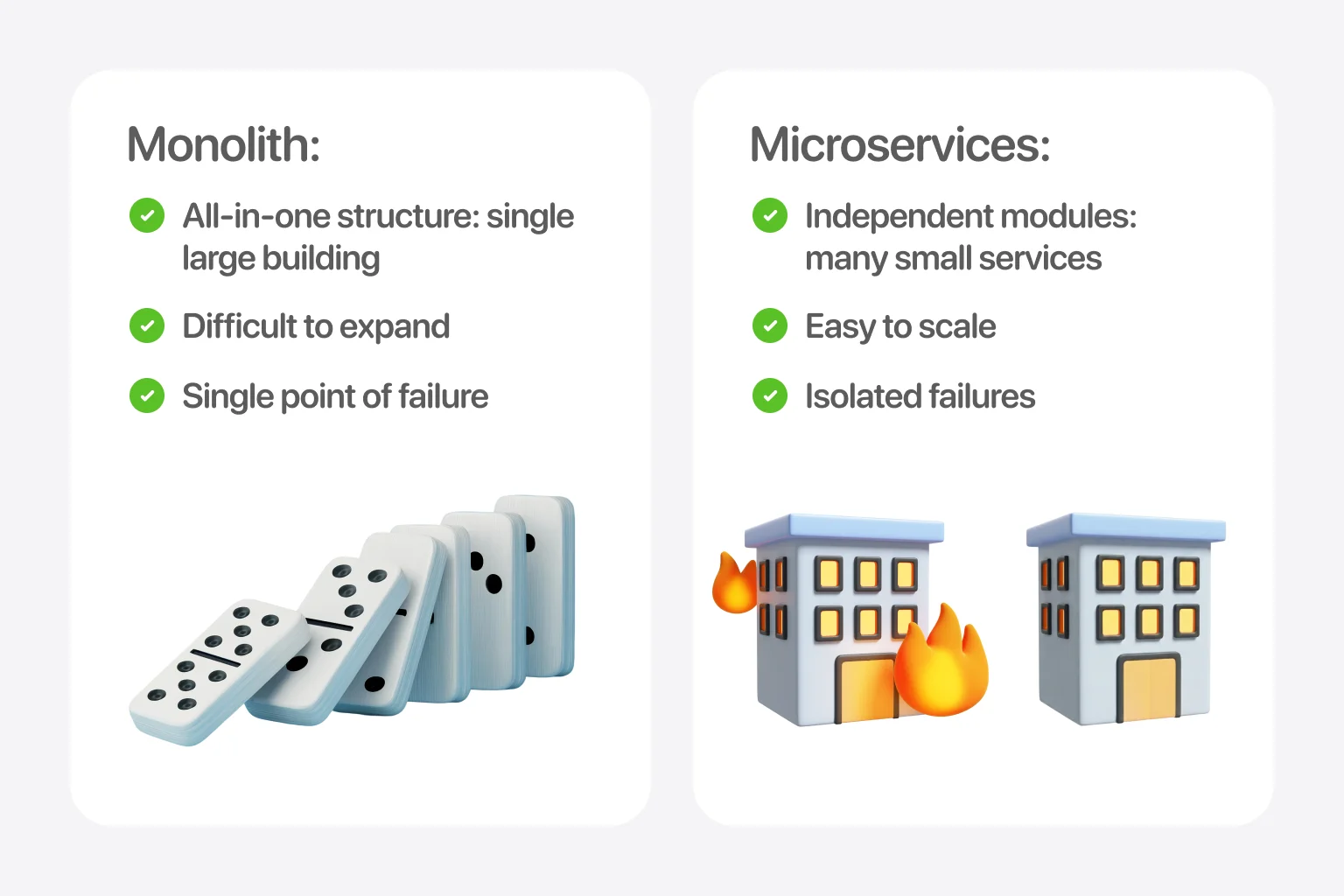

Traditionally, most software systems have been built as monoliths. Like any traditional structure, a monolith is a single system where all components are tightly interconnected. Imagine a large house where all the rooms are linked. It’s convenient: everything is under control and in one place. But if a pipe bursts or a fire breaks out in one room, the entire house could collapse.

Microservices, on the other hand, are like a modern town with autonomous buildings. Each microservice is a separate house with its own electrical system, water supply, and communications. If something breaks in one house, the others continue to function without issues.

“Strong systems aren’t the ones where everything depends on everything else — they’re the ones where each part can stand on its own.”

Key differences

Now that you know the basics about monoliths and microservices, the question arises, “How do I choose between them?” The choice determines whether a single bug crashes your entire system or just one isolated feature. Let’s break down the practical differences here.

Design

In terms of design, a monolith is like a large building in which separate rooms or floors handle functions, but everything is within a single structure. Meanwhile, microservices presuppose that each module operates independently, like a small building connected to the city’s infrastructure via APIs.

The catch with monoliths is that without formal walls between different parts of the system, it’s tempting to take shortcuts. And those shortcuts have a way of becoming permanent fixtures you didn’t plan for. With microservices, the real challenge comes when a design mistake is built into multiple services — fixing it later can become a major headache.

Business functions

Monolithic architecture means that one massive application handles all business functions. In microservices, each module handles one specific function (e.g., one house serves clients, another processes orders, and a third handles payments).

The downside of a monolith for business functions is that you’re only as fast as your slowest-moving piece. Imagine you need to update your pricing logic, but now the release is stuck waiting on a compliance change or a payment system fix. With microservices, business functions can move at their own pace. But here’s what people don’t always expect: now you need way more coordination. Meetings multiply, and miscommunication becomes costly.

Flexibility

A static structure, aka a monolith, is hard to expand because building a new floor requires reinforcing the foundation and walls of the entire building. As the system grows, people become more cautious — experiments feel riskier, and the appetite for frequent changes fades.

On the other hand, microservices architecture lets you build new “houses” wherever needed without a general reconstruction of the whole city. However, this only works if you design things well up front. Poorly thought-out service boundaries actually create more coordination headaches, not fewer. You end up with teams constantly negotiating changes and dependencies instead of moving independently.

Scaling

Monolith scales as a single unit, so you must allocate resources to the entire project. If your checkout process is getting hammered, for instance, but the rest of your app is barely used, you still have to spin up entire copies of the application. That means you’re paying for a lot of capacity you don’t actually need.

Using microservices, you can increase the power of a specific service experiencing high load without touching other parts of the system. It’s more efficient and can save you real money. But now you need to actually know what’s happening across your system. Without good monitoring and a solid understanding of how things connect, you can easily make the wrong scaling decisions or create new bottlenecks you didn’t see coming.

Errors

In a monolithic architecture, even a single code error can bring down the entire system. It’s like with dominoes, one failure triggers others. A bad deployment, a memory leak, or one slow database call can bring down the whole system. The upside is that all logs and stack traces are in one place, making debugging much more straightforward.

Microservices are isolated. An error in one service won’t touch the others, and the system keeps running. But now failure handling becomes something you have to actively design for. Was it a network hiccup? A timeout? Which service in the chain actually failed? You’re hunting through distributed logs and tracing requests across multiple systems, which is a different kind of challenge.

Greatness lies in structure, not size

Big projects don’t usually fail because the team lacks talent. They fail because complexity outpaces the team’s ability to manage it. Traditional monolithic architectures face slow releases, dependencies hidden in unexpected places, and wasteful scaling. Under such conditions, even one failure can take down everything. Microservices could be a reasonable solution: they isolate functionality, enable independent scaling, and offer faster iteration and better fault tolerance. However, they require careful design, monitoring, and coordination to avoid new pitfalls. It’s clear that the architecture matters, but so does how intentionally you approach it.

in your mind?

Let’s communicate.